By Ariana Besse (B.Phty Hons)

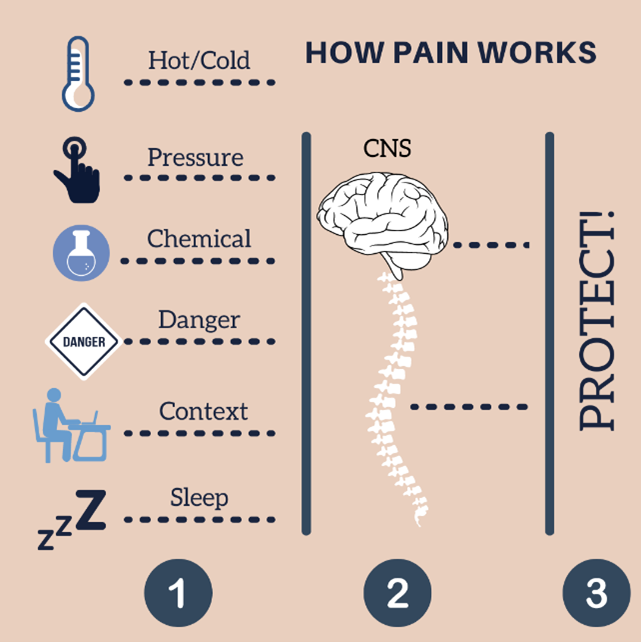

A recap of the first blog in this 4-part series: Pain is the output from a combination of inputs from receptors in the periphery (i.e. thermal, chemical, mechanical, nociceptive) and the context of the experience e.g. memory, previous experiences, belief. There is no one pain receptor or nerve. The brain computes these inputs, decided whether the stimulus is threatening, and we feel pain as the output.

A recap of the first blog in this 4-part series: Pain is the output from a combination of inputs from receptors in the periphery (i.e. thermal, chemical, mechanical, nociceptive) and the context of the experience e.g. memory, previous experiences, belief. There is no one pain receptor or nerve. The brain computes these inputs, decided whether the stimulus is threatening, and we feel pain as the output.

When is our Pain Output Misrepresented?

When you have been in pain for a long time, from a few weeks up to years, it doesn’t take much to flare up that injury again. E.g. in a person without an injury, there are (figuratively) one hundred little nociceptors at the site of injury (ankle, knee, back). Whereas in someone with pain, they may have 200 nociceptors in that area of injury. Henceforth, they have more input from that area due to the higher number of receptors responding. The body changes over time. The body has had input from that area for a substantial length of time, so it increases the “watchers” to that area. This is a way of saying “I’m concerned about this area, keep a close eye here”. We then become more sensitive and “better” at protecting ourselves.

Another thing that can happen is that, not only do you get more receptors to that area, the threshold for those receptors to fire can decrease before they send off their warning signal. E.g. in a person without an injury, they would have to fill (figuratively) their receptor’s capacity to 1L before they fire. Whereas, someone with an injury that has been experiencing pain for a longer period of time may only have to fill their receptor to 0.5L before it fires. So they both have a higher number of receptors and a decreased threshold at which they fire at.

Another thing that can happen is that, not only do you get more receptors to that area, the threshold for those receptors to fire can decrease before they send off their warning signal. E.g. in a person without an injury, they would have to fill (figuratively) their receptor’s capacity to 1L before they fire. Whereas, someone with an injury that has been experiencing pain for a longer period of time may only have to fill their receptor to 0.5L before it fires. So they both have a higher number of receptors and a decreased threshold at which they fire at.

ANOTHER Analogy from Matt

Let’s talk about the car alarm. You have this beautiful car that you really want to take care of, and someone walks past and scratches it with a key. And nothing happens, no alarm, because it’s not sensitive enough. So you fix this, dial up the “sensitivity” of the alarm. If this repeatedly happens over time, you dial up the alarm so much that eventually just another car driving past with a loud exhaust will set off the alarm. At that point, we have a mismatch between damage to your car and the alarm’s response. There is no change to your car’s “tissue”, it is the same as it was before. It needs a lot less input than it would have before. This is your body’s response with an increase in nociceptors in an area and a decrease of the threshold at which they fire at.

Let’s talk about the car alarm. You have this beautiful car that you really want to take care of, and someone walks past and scratches it with a key. And nothing happens, no alarm, because it’s not sensitive enough. So you fix this, dial up the “sensitivity” of the alarm. If this repeatedly happens over time, you dial up the alarm so much that eventually just another car driving past with a loud exhaust will set off the alarm. At that point, we have a mismatch between damage to your car and the alarm’s response. There is no change to your car’s “tissue”, it is the same as it was before. It needs a lot less input than it would have before. This is your body’s response with an increase in nociceptors in an area and a decrease of the threshold at which they fire at.

There are plenty more analogies we can use to explain pain, but here is just one. Stay tuned for the next video and blog discussing the topic: “Is pain really in your brain?”

References:

- Butler, D.S., & Moseley, G.L. (2016). Explain pain(2nd [updated] ed.). Noigroup Publications.

- Moseley, G.L., & Butler, D.S. (2017). Explain pain supercharged: the clinician’s manual. Noigroup Publications.

- https://cor-kinetic.com/have-we-ballsed-up-the-biopsychosocial-model/

- https://www.iasp-pain.org/

- https://www.noigroup.com/resources/

- https://cor-kinetic.com/blog/

- http://www.greglehman.ca/blog

For more information, check out the following video of Matt and Zac.